August 31, 1981 People

Magazine Article

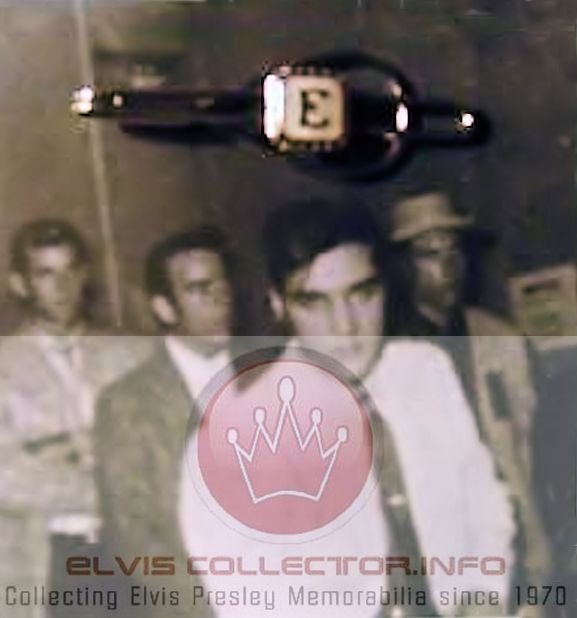

1968 photograph of crowd clapping as Elvis, not in this shot, was singing an "Elvis altered" version of Happy Birthday during a break in rehearsals of what would be the 1968 Singer TV Special entitled "Elvis".

Col. Parker Made Elvis

Golden; Now a Memphis Court Wonders If He Fleeced Him Too

Everyone called the relationship as close as

that of father and son. Indeed, the legend grew from the start that Col. Tom

Parker, a colorful ex-carny, had as much a paternal as a financial interest in

the truck-driving lode of inchoate talent named Elvis Aaron Presley. Parker

masterminded him into the King, the biggest solo act in show business, and if

sometimes the Colonel seemed to be slicker than a hound dog's tooth, well, he'd

made Elvis a millionaire, hadn't he?

True, but if the King is now resting in peace, those who survive him surely

aren't. Almost four years to the day since Presley died, his fortunes are now

being debated in a bitter probate court fight that pits Parker against

Presley's sole heir, his daughter, Lisa Marie, 13. The allegations filed by

Lisa's court-appointed guardian include charges that Parker, 72, enriched

himself by mismanaging Presley's career and cutting the singer out of millions

of dollars by negotiating unfavorable agreements.

After a court hearing in Memphis—ironically held the weekend thousands of

mourners gathered there to commemorate the Aug. 16 anniversary of Presley's

death—Judge Joseph W. Evans wrote in a heated opinion that "the compensation

received by Colonel Parker is excessive and shocks the conscience of the

court." Evans then ordered the Presley estate to cease all dealings with

Parker, institute litigation against him to recover a yet to be determined sum,

and continue investigating an array of seemingly disadvantageous contracts

negotiated by Parker, chief among them Presley's pact with RCA Records.

However the case is eventually settled, the episode has renewed disturbing

questions about Parker's past and his involvement with Presley—both the man and

his estate. Although the Colonel (the honorary title was bestowed by a

Tennessee Governor) maintains he is the son of a West Virginia "carnival

family," the court records reveal he was in fact born Andreas Cornelis van

Kuijk in Breda, Holland and came to America in 1929, at age 20. His foreign

birth supports speculation that the reason Presley never accepted

multimillion-dollar overseas gigs was Parker's inability to secure a U.S.

passport. He spent his youth working for the Great Parker Pony Circus before

segueing into C & W management. Parker had already handled Eddie Arnold and

Hank Snow when, in the mid-'50s, he first heard a young singer from Tupelo,

Miss, belting out rockabilly tunes around the South. By November 1955, Parker,

then 46, signed the 20-year-old Presley to an exclusive management contract.

Parker's entrepreneurial wizardry during the early years is not in dispute. He

clearly orchestrated Presley's transformation from an ungroomed rock pioneer

into a slick Vegas showroom entertainer who made 33 mostly B movies over the

years. For his part, Presley, at least in public, gave Parker full credit for

every step of his success.

Recently, however, Presley revisionists have begun to downgrade Elvis' real

closeness to the Colonel. Larry Geller, a longtime member of Elvis' Memphis

Mafia, observes: "Elvis respected the Colonel for his ability to

manipulate lawyers, companies and situations, but he felt very uncomfortable

around him." And rock historian Albert Goldman, who will this fall publish

an exhaustive 600-page biography titled Elvis, says, "In the 21 years they

knew each other, Elvis and the Colonel never had dinner together once."

Friends also recall that Parker came to Elvis' funeral dressed in a Hawaiian

shirt and baseball cap and studiously avoided looking at the casket.

The quality of the personal relationship the two men shared may never be fully

understood, but now the Colonel's business dealings have come under scrutiny as

well. In May 1980, Memphis entertainment lawyer Blanchard E. Tual, 36, was

appointed by the probate court to represent Lisa Marie after the executors of

Elvis' will sought clarification of their dealings with Parker. Once Tual began

his probe, the Colonel's role became increasingly suspect. For instance, during

the first 11 years he managed Presley, Parker took a high but not unprecedented

25 percent of the singer's earnings. Tual points out that the Colonel neglected

to register Elvis with a musical licensing firm, thereby forfeiting his client's

share of songwriters' royalties. Yet in agreements signed on Jan. 2, 1967,

Parker doubled his cut from Presley's earnings. Elvis signed away a flat half

of his grosses, a cut Tual says was "exorbitant, excessive, and

unreasonable...and raises the question of whether Parker has been guilty of

self-dealing."

Soon thereafter Parker contracted Presley to play Vegas' International Hotel

for what Tual calls "a surprisingly low figure...$100,000 to $130,000 a

week: a price that was soon surpassed by acts of far less commercial

value." Tual quotes Alex Shoofey, who was manager of the hotel at that

time, as boasting that the arrangement was "the best deal ever made in

this town." Parker, according to Shoofey, had developed a liking for

casino action and "was one of the best customers we had. He was good for a

million dollars a year." Observes Tual acidly: "The impropriety of a

manager losing such sums in the same hotel with which he has to negotiate on

behalf of his client goes without saying.... [He] sold Elvis short."

Even more damning, in Tual's judgment, is a baroque series of contractual

maneuvers all dated March 1, 1973. By then Elvis' health had begun to fail, and

he was in the throes of his divorce from Priscilla Beaulieu Presley. One

contract sold to RCA all the King's master tapes for $5 million, split 50-50

between Parker and Elvis. "Elvis was only 37 years old," says Tual,

"and it was illogical for him to consider selling an almost certain

lifetime annuity from his catalogue of over 700 chart songs. The tax

implications alone should have prohibited such an agreement..." In fact,

of his $2.5 million from RCA, Presley kept only $1.25 million after taxes.

There was also a new seven-year contract with RCA that Tual criticizes on two

counts: "Elvis' royalty rate was only one-half of what other major artists

of the day, such as the Rolling Stones, Elton John or the Beatles, were

receiving. Another glaring deficiency...was that it contained no audit

clause." He adds: "RCA has denied the estate's request to audit the

period from March 1, 1973 to Jan. 31, 1978 due to nonobjection of accountings

by Colonel Parker." Tual contends that if an audit is ever conducted for

that period, Presley's estate will reap a windfall in unpaid royalties.

Finally, there were three separate letter agreements on the same March 1 date

in which RCA committed itself to pay Parker, for his merchandising and

promotional expertise, a total of $1.75 million, plus 10 percent of the net

profits from any Presley tours, over seven years. Presley okayed each of the

letters, but received not a penny. "Even though Elvis acknowledged the

letter agreements," observes Tual, "they constitute a clear conflict

of interest and a breach of Colonel Parker's fiduciary trust...Colonel Parker

could not possibly deal with RCA at arm's length on Elvis' behalf when he was

receiving that much money from RCA."

Tual concludes that both RCA and Parker acted in collusion against Presley's

best interests. "These actions against the most popular American folk hero

of this century," he says, "are outrageous and call out for a full

accounting from those responsible."

RCA denies any wrongdoing, and Parker told PEOPLE, "Elvis knew that I

provided services for others. He was satisfied with our arrangement, and it worked."

Parker also issued a broadside condemning "the unjust allegations that not

only attack my name and reputation, but also are unfair and insulting to the

memory of Elvis and his father, Vernon [who died in 1979]. I highly respected

Elvis Presley, and I have made every effort to honor his name and preserve his

memory with dignity." Not unexpectedly, the Colonel hints darkly at

pursuing "legal actions" against his foes.

Retorts Tual, who has been asked by the court to continue his investigations:

"Elvis Presley has been dead for four years now. I am not crusading for

anybody. I'm looking out for the interests of his little girl—I think she's

entitled to the benefits of her father's efforts and artistic talents."

(Lisa lives in Beverly Hills with Priscilla, 36.) The lawyer is doubly

concerned because the IRS recently hit the Presley estate with a back tax

assessment that, if upheld, would take away $14.6 million of the estimated $25

million estate.

In Memphis, the now familiar hucksters of Presleyana are still hawking their

shabby wares outside Graceland. Fans like Jody Compton still keep their evening

vigils at the gates. "Nighttime," she says, "is the most

beautiful time to be there for the lights, the magic—for being able to

visualize Elvis doing the things he did at night. He's not really gone, you

know."

Not as long as LPs and tapes continue to be sold. But the never-ending

revelations of the frightful price Presley paid for his fame give sad lie to

the last of his more than 90 gold singles. Released in 1977, just months before

his death, it was titled My Way. The truth was, even to his own detriment, he

did it the Colonel's way.